Earl Carroll, LaVerne Drake, and Robert Phillips were already singing together in the early 1950's as the Carnations, whose lineup also included "Cub" Gaining. Carroll and Phillips were nearly as close as brothers, Carroll having been taken in by Phillips' family after the death of his own mother. The group, based in New York's Harlem, in the area around 131st St. and Seventh and Eighth Avenues, had an energetic approach to music, but somewhat threadbare harmonies, and they were popular at dances held at the local public school they all attended. Their main influence was the Orioles, whose slow romantic numbers went over very well with the group members and the audiences of the period. Carroll's own musical roots included gospel, specifically the Five Blind Boys, the Swanee Quintet, and the Soul Stirrers, but also R&B vocal outfits such as the Clovers, the Ravens, the Swallows, and the Five Keys.

The Carnations were heard in a performance at Public School 43 by Lover Patterson, a one-time associate of the Orioles who had organized a group called the Five Crowns (whose 1958-era membership would become the new Drifters, of "There Goes My Baby" fame), who was impressed enough with their singing to introduce group to Esther Navarro, a secretary for the Shaw Artist Agency who also wrote songs.

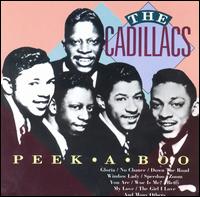

The audition itself brought about changes in the Carnations' lineup. Baritone Bobby Phillips wanted to switch to bass, partly to see if the novelty value of a 5' 4" bass singer would have some value (most basses were big guys), but Cub Gaining didn't like the idea and quit before the audition. Patterson replaced him with James "Poppa" Clark of the Five Crowns and Johnny "Gus" Willingham. It was this group -- Earl Carroll, lead tenor, LaVerne Drake, tenor, James Clark, tenor, Johnny Willingham, baritone, and Bobby Phillips, bass -- that auditioned for Navarro. They were duly signed but had to give up their name, as the Carnations was already being used by a professional outfit. The Cadillacs was chosen for its association with automotive elegance and to separate the group from the spate of bird and flower names that were common among singing groups.

The group brought a pair of songs, Navarro's "Gloria" and Patterson's "I Wonder Why," to Jubilee Records, an independent outfit owned by former bandleader Jerry Blaine. Their first single was in stores by the end of July, 1954, and it proved to be a regional success, with strong sales on the East Coast from Baltimore to Boston, especially (no surprise) in New York. Patterson's more uptempo "I Wonder Why" had more success than the more restrained and romantic "Gloria." By the time of the release of the group's second single, "Wishing Well," issued later that summer, the lineup had changed, with James Clark and Johnny Willingham replaced by baritone Earl Wade and tenor Charles "Buddy" Brooks.

The group experienced modest success during the latter part of 1954 and early 1955, and then they had their breakthrough record, "Speedo." There have been several stories associated with the origins of the song, all of which surround Earl Carroll's attributes -- Carroll has claimed that it originated with a nickname he got as a child, but also said that the beat and background were influenced by the group's appreciation of a Regals song called "Got the Water Boiling." Esther Navarro, whose name is signed to the song as writer, claimed at the time that it derived from Carroll's derisive nickname, "Speedy," earned by his slow-moving demeanor -- she claimed that he said to her, "They often call me Speedy but my real name is Mr. Earl."

The song was recorded in September of 1955, and released in October of that year. It became a monster hit, but only after laying dormant for weeks. The turning point came when Cleveland-based disc jockey Alan Freed booked the group onto his Christmas show at the Academy of Music. The group by that time was completely professional, and had added dance routines choreographed by Cholly Atkins, who later trained most of the Motown acts in their stage presentations. The group swept the board during the two weeks of appearances in the Freed show, which, itself was a major turning point in the history of rock & roll -- there had been showcases of that kind going on for several years, but mostly before black audiences; the Freed show broke the theater's box-office record, and in the process drew in a major contingent of white teenagers.

"Speedo" finally broke out in early December, and it entered the Billboard pop charts before it reached the R&B charts, something that had never happened before with an R&B single. The music industry began taking notice not only of this phenomenon, but also of the Cadillacs. The song rode the charts for four months, well into 1956, by which time the Cadillacs were established as one of the top R&B groups in the country. They also had a membership change early in that year, with Jimmy Bailey replacing founding member LaVerne Drake. Their attempts at a follow-up hit failed despite some initial encouraging signs from the trade papers, but this didn't slow their momentum on stage -- they remained one of the most heavily and prominently booked groups among the package tours that were the norm, and the bookings were still good into the late winter of 1957.

Unfortunately, nothing was that straightforward for the group itself. At some point, they split with Esther Navarro, and the group also split into two rival sets of Cadillacs. Earl Carroll led "The Original Cadillacs," as they became known -- consisting of Carroll, Charles Brooks, Bobby Phillips, and Earl Wade -- while Navarro had Jimmy Bailey leading Bobby Spencer, Bill Lindsay, and Waldo "Champ Rollow" Champen under the name the Cadillacs. The groups both continued recording, both on Jubilee (which was caught in the middle of the dispute), and effectively cancelled each other out.

Navarro's Bailey-led Cadillacs (who only recorded once officially, doing "My Girlfriend" in May of 1957) went on the road in an abortive attempt to carry on, but they were pulled out of the late-1957 package tour before it was half over. By November of 1957, the two groups had made a sort of peace -- Champ Rollow and Bill Lindsay were out, and Carroll, Bailey, Brooks, Phillips, and Wade were working together in the studio as the Cadillacs. Brooks was soon replaced by Bobby Spencer, but there were other changes as well -- Earl Carroll was pushed into the background of the group's vocals by Jimmy Bailey and Bobby Spencer. Of course, it didn't matter that much, because in their search for a sound that would sell, the group had changed into a comedic doo wop outfit in the mold of the Coasters, specializing in humorous novelty numbers. They hardly resembled the outfit that Earl Carroll had co-founded in the early 1950s.

The sad thing, in some respects, is that this worked. They were back on the national charts for the first time in over two years in October of 1958 with "Peek-A-Boo," a sort of "Yakety Yak"-type number that made the Top 30 and gave the group a new lease on life as a concert attraction. Having succeeded once with a comic novelty tune, they mined this vein again with a pair of singles, "Jay Walker" and "Please Mr. Johnson," both of which were recorded early in 1959 and featured (in very effective performances) in the 1959 Alan Freed-starring jukebox classic Go Johnny Go, which also featured Jimmy Clanton, Sandy Stewart, Chuck Berry, Jackie Wilson, Eddie Cochran, Ritchie Valens, and Jo-Ann Campbell.

The group's string of hits had ended, however. Earl Carroll left the group that he had founded in 1959 -- the Cadillacs kept working for a few more years, recording unsuccessfully for a number of labels before packing it in during the early 1960s. Carroll fared reasonably well, however, remaining in music and eventually joining the Coasters in 1961, where he remained for more than 20 years. He later reformed the Cadillacs, with Bobby Phillips the only other veteran member of the group, and he kept the new group going throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, even doing a well-received comeback record early in the '90s