Norman Petty

| Mood Indigo | |

| On the Alamo |

One of the most important and, in some senses, controversial rock'n'roll producers of the late 1950s, Norman Petty's name will forever be inextricably linked with that of Buddy Holly. At his Clovis, New Mexico studio, Petty produced many of Holly's greatest recordings, and received co-author credit for much of Holly's material. He also recorded on his own, and had some significant success with artists in the 1960s that owed much to the Holly sound, particularly Jimmy Gilmer & the Fireballs. He would never approach the greatness, or sales, of the music he made with Holly, however.

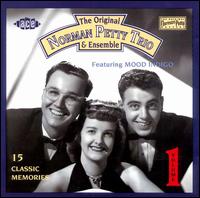

Born in Clovis, a small town near the New Mexico-Texas border, Petty formed the Norman Petty Trio with his wife Vi on piano and Jack Vaughn on guitar; Norman played organ. The Norman Petty Trio made some instrumental pop records in the 1950s and had a little success with "Mood Indigo," and Petty was becoming known within the industry for his songwriting, particularly with "Almost Paradise" (covered by Roger Williams). In 1955 Petty founded his own studio in Clovis to record musicians in the area, which despite its isolation from recording industry centers had a lot of country and rock talent. It was at Petty's studio that Roy Orbison did his first recordings, even predating Orbison's Sun Records sessions.

Petty landed major early rockabilly hits with the Rhythm Orchids, whose vocalists were Buddy Knox and Jimmy Bowen. Petty produced Knox's "Party Doll" and Bowen's "I'm Sticking with You," both massive hits, which were issued under Knox's and Bowen's name respectively although they were both recorded by the same musicians (the Rhythm Orchids). Petty was unusual for the time in that he charged by the session rather than by the hour, which could make musicians feel more comfortable about taking their time to get things the way they wanted.

In late 1956 Buddy Holly, after just a few releases for Decca that had been recorded in Nashville, was dropped from the label. He continued to pursue his career ardently, however, and had met Petty in the course of cutting demo records, as Clovis was within driving distance of Holly's hometown of Lubbock, Texas. One of the songs Holly and the Crickets recorded in early 1957 was a remake of "That'll Be the Day," which Holly had already recorded, in a version he was not pleased with, on Decca. Petty later said he took the later, superior version of "That'll Be the Day" to Coral Records--ironically, a Decca subsidiary--whose Brunswick imprint issued it in mid-1957. It was a huge hit, and until late 1958, Holly and the Crickets would do most of their recording at Norman Petty Studios, with Petty producing.

Many of the records produced at Petty's studios--not just Holly's--had what's now known as a "Tex-Mex" feel. There were strong hints of Latin rhythms, country and western music, and some western swing. The rhythm guitar tended to be strummed quickly and have a lot of presence on the records, and the lead guitar often had a clear and sharp quality. The sound was often rockabilly in flavor, but had a cleaner and more polished feel than the sessions cut at Sun in Memphis and other regional studios recording Southern rockabilly. Buddy Holly's recordings represented the apogee of this approach, towering over the other Clovis acts because of Holly's amazing songwriting and singing, as well as the instrumental skills of the Crickets.

Petty's contributions to Holly's records were considerable. He recorded Holly with session backup vocalists to fill out the vocal arrangements, and sometimes played keyboards on the sessions themselves (as did his wife Vi). He was willing to spend a lot of time with the Crickets in the studio perfecting their performances, and let the musicians record late at night and early in the morning when the studio wasn't booked and they wanted a lot of time to work things out. He used a live echo chamber to give the sound some reverb, but not so much that it sounded drenched in echo, as records sometimes did when tape-delay echo was used. On "Peggy Sue," he switched the echo chamber on and off to create a rolling sound on the song's memorable drum patterns. His skills with microphone placement (he would use a small mic between the strings and the body of a standup bass to record the percussive rattles of the instrument, and other mics to pick up the notes) and sound balance gave the records a sound that was both powerful and uncluttered. The Crickets were also one of the first rock acts to effectively use overdubbing.

Petty is also credited as co-author on many of Holly's recordings. The extent of this role, unlike his others, has been questioned. Some of the Crickets have said that Petty's songwriting contributions were minor, sometimes so minor that they did not deserve a credit or a cut of the publishing. It was certainly common practice in those days (and, to varying degrees, in other eras) for a producer, or even record label owner or disc jockey, to take a part of the songwriting royalties even when they had little or nothing to do with the actual composing.

Petty also became manager of the Crickets in mid-1957. The balance of egos in the group was already precarious, since Holly was the unquestioned star, although this was partially alleviated by issuing some recordings under Holly's name, and some under the Crickets'. But by late 1958 a wedge had been driven between Petty and Holly, and between Holly and the Crickets, which was probably at least partially Petty's fault. As manager, producer, and co-songwriter, Petty had a lot of control over the Crickets' finances.

Particularly after he married Maria Elena Santiago, who worked in music publishing, Buddy had a lot more smarts about the music business and was determined to get more control over his income. Holly decided he wanted to leave Petty and move to New York. The other Crickets waffled, and Petty talked them into staying with him and leaving Holly. Buddy did move to New York with his wife, splitting from the other Crickets. He had hopes of getting the band back together, although he toured with other musicians using the Crickets name, but died in early 1959, before a reconciliation could be effected.

It has been speculated that one of Holly's main motivations for undertaking a winter tour of the midwest in early 1959 was because he was having trouble getting access to his earnings, much of which still remained tied up with Petty. It's probably going too far to blame Holly's death in a plane crash during that tour on Petty; no one expected or wanted a fatality. However, because of difficult-to-answer questions about where the money was going and should have been gone, it's safe to say he's not held in universally high esteem by big Holly fans.

Petty was not done with Holly after his death, either. In the 1960s he overdubbed some of Holly's demos and early recordings with additional instrumentation, usually by regional group the Fireballs, ostensibly to make the tracks presentable for the commercial market. Many listeners legitimately question not only the quality of the overdubs, but the need to overdub the original recordings in the first place. Trying to sort out the undubbed or overdubbed states of various Holly tracks bearing the same name, on a plethora of reissues, compilations, and bootlegs, is a sure way to induce a headache.

Petty continued to operate his Clovis studios in the 1960s, and much of the time it was obvious he was striving for a Buddy Holly-type sound. The problem, of course, was that none of his proteges could approach Holly in singing, songwriting, and vision. He had his most success with the Fireballs, who had a few instrumental hits (like "Torquay") that were textbook Tex-Mex rock.

The Fireballs also recorded vocal numbers too, often featuring Jimmy Gilmer as lead singer; Gilmer had a #1 hit in 1963 with "Sugar Shack," and the Fireballs got a Top Ten vocal hit in 1967 with "Bottle of Wine." Petty also recorded folk and rock with the obscure but influential singer Carolyn Hester in the 1950s and 1960s, and did a superb single with soul singer Arthur Alexander, "You Don't Care"/"Detroit City."